to top

Thesis Topic

If ink and brushwork constitute the most essential “backbones” of Chinese painting, why and how did “boneless landscape” (mogu shanshui), a genre that uses color washes to form the object without relying on ink outlines, enjoy sudden popularity in the 17th century? The field of Chinese landscape painting study has mostly neglected this question due to the oversimplified perception that paintings in color were generally considered decorative or vulgar by educated elites compared to ink monochrome paintings. Yet many celebrated artists and patrons created or collected boneless landscape painting. This raises another important question: How did the educated elite reconcile the perceived conflict between using color and its disparagement, ultimately integrating it into 17th century elite culture? Through analysis of paintings by three leading practitioners: Dong Qichang (1555-1636), Hu Yukun (1607-fl.1687), and Lan Ying (1585-ca.1664), I argue that the so-called Tang boneless landscape was an invented tradition. It represents a significant shift in taste, where color was elevated from a secondary decorative element to a primary medium for self-expression and self-distinction. This subjectivity inherent in color allowed scholars and artists to infuse the art historical idea with the cultural and social value of the time, fulfilling their personal and communal aspirations.

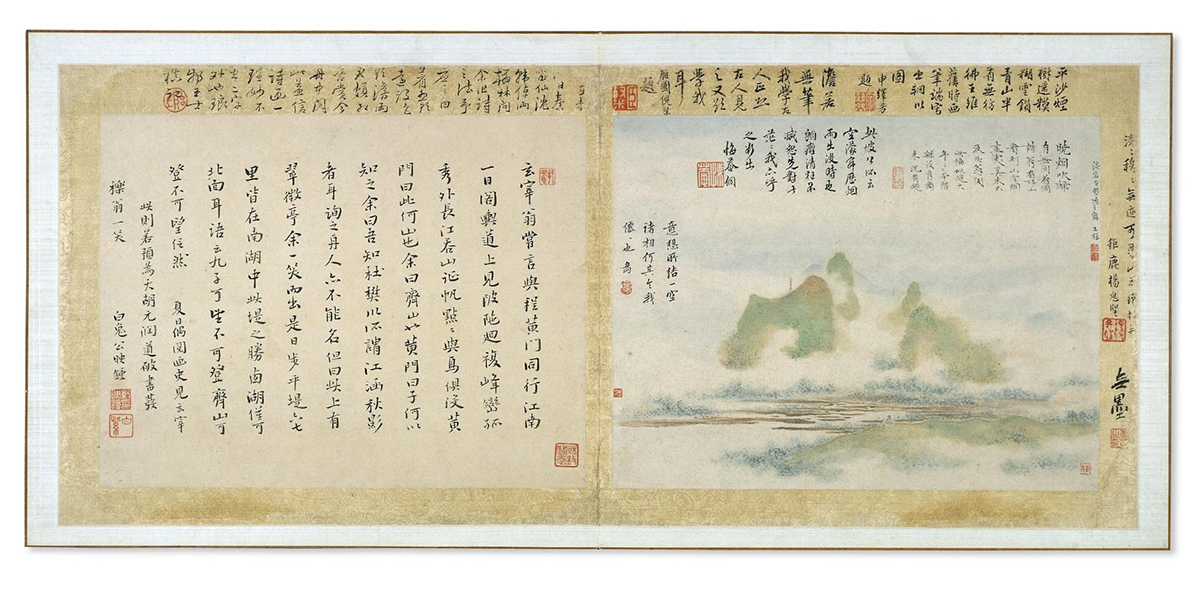

The first case study examines the origins of boneless landscape. Dong Qichang, the celebrated scholar-official and arbiter of taste, synthesized the archaic “red and blue” coloration, exotic Japanese paintings, and visual references from literati painting traditions to formulate the concept of the “Tang boneless method”. Guided by the artistic theory of qi-zheng (eccentricity-orthodoxy) dialectic, Dong embraced the eccentric color style within his literati aesthetic frameworks. This canonization led his followers to adopt the color style in their own painting practice.

By utilizing the semiotics of “color” and “boneless”, Hu Yukun created a tripartite analogy in his landscape, connecting “color/boneless” in painting, “brushless/overtone” in poetry, and the “form (se)/emptiness (kong)” in Buddhism. This philosophical analogy not only reflected the poetry theory of his patron but also prompted viewers toward intellectual and aesthetic enlightenment in both painting and poetry writing.

Lan Ying’s Daoist paradise, rendered in the boneless technique, offered not just aesthetic appeal but also physical and mental solace to his patrons during the political chaos of the Ming-Qing transition. The precious pigments and the composition of multi-tiered mountains served as a metaphor for Peach Blossom Spring, an artful space for escape. They also embodied the body’s interior, acting as a visual aid for Daoist meditation and therapeutic exercise.

As the first English-language monograph on this topic, this study explores the interdisciplinary interactions among painting, poetry, philosophy, religion, and material culture in the development of the boneless landscape. It enriches the study of color and colored painting and offers a new lens to examine the literati culture and socio-cultural diversity of the 17th century.