to top

Thesis Topic

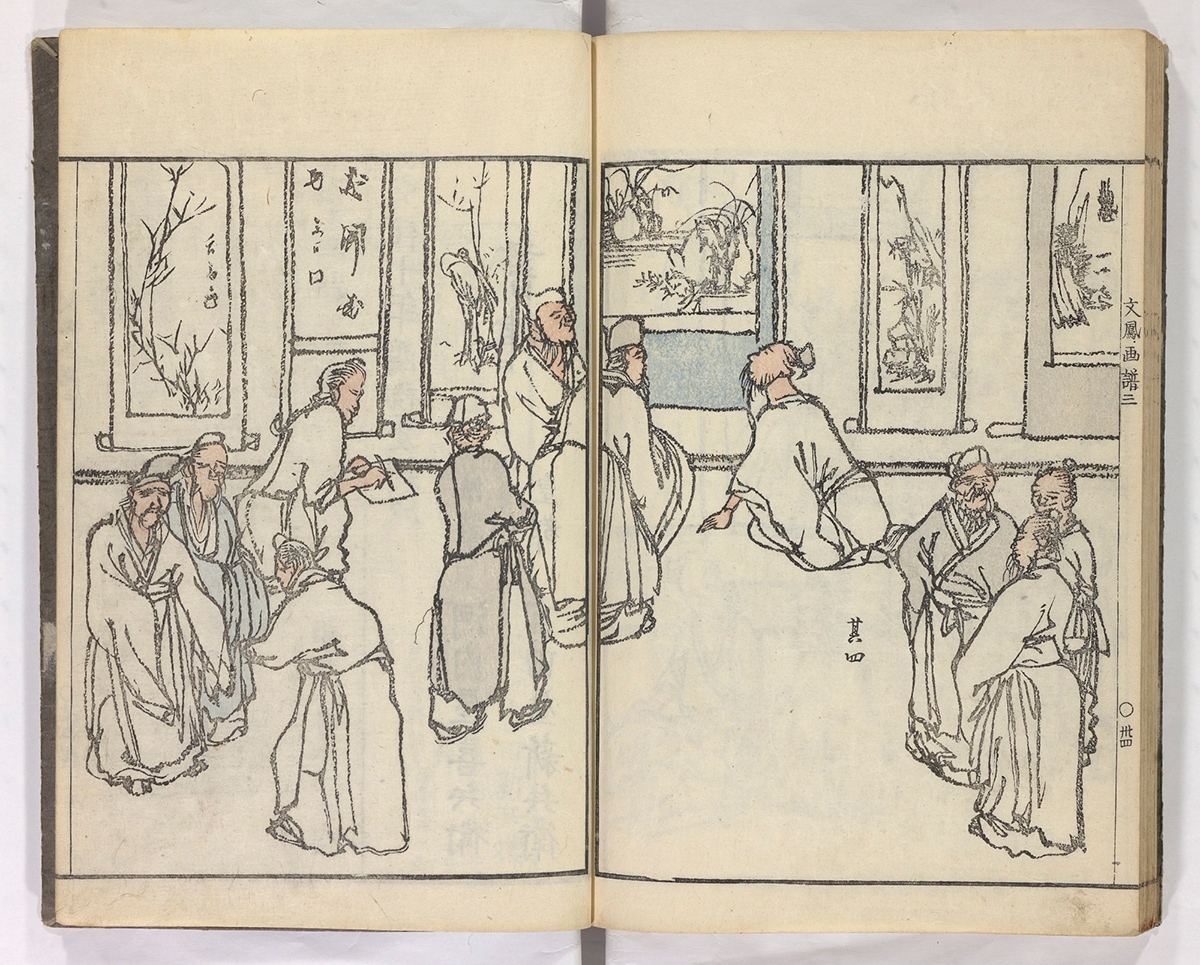

This dissertation examines woodblock-printed painting manuals in Edo Japan (1603–1868) to explore how they reflected the Japanese understanding, reception, and manipulation of Chinese art from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries. I approach these manuals as a publishing phenomenon driven by a growing public interest in artistic refinement, reflecting early modern Japan’s unprecedented, society-wide engagement with Chinese cultural signs—both as symbols of high culture and as concepts continually challenged and redefined. As a result, Japanese engagement with Chinese art—selective, strategic, interpretive, and at times deliberately misconstrued—became extremely active. These shifting perceptions, shaped by the socio-cultural context of early modern Japan, continue to shape contemporary art-historical scholarship.

In this dissertation, painting manuals refer broadly to woodblock-printed books that center on images and convey painting techniques or knowledge. The term serves as a shorthand for a wide range of formats—primers, copybooks, compendiums, catalogues—that often blur genre boundaries. Between the seventeenth and mid-nineteenth centuries, Japan experienced an unprecedented boom in such publications, with at least several hundred—and by some estimates as many as 1,500—titles offering access to painting skills and knowledge, far surpassing other early modern societies in both volume and diversity. I argue that in early modern Japan, painting manuals became a vital space where artistic refinement was constructed and contested through engagement with the reading public. Furthermore, I contend that the prominence of “Chinese-ness” in this publishing phenomenon reflects not mere continental influence, but rather the negotiation of powerful cultural signs that shaped taste and authority.

Organized into a broad chronological framework, this dissertation examines the evolving nature of painting manuals and the place of Chinese and “Chinese-style” art throughout the Edo period. Chapter One unpacks how mass-re-produced Chinese painting manuals—available but little discussed in Japan during the seventeenth century—became esteemed cultural products and a focal point of artistic discourse from around the turn of the eighteenth century. Chapter Two situates the eighteenth-century boom of Chinese-inspired Japanese painting manuals within the ongoing struggle for cultural authority, examining how they negotiated “Chinese-ness” and reshaped notions of “Chinese-style” painting. Chapter Three explores the rise of sketchbooks between the late eighteenth and nineteenth century as a distinctly Japanese genre, embodying new artistic tastes and values that challenge the dominance of Chinese signs and their proponents in the cultural and social hierarchy. Chapter Four examines the prevalence of printed albums and anthologies of painting in the late Tokugawa period that, in sharp contrast to sketchbooks, featured precise reproductions of works by past masters and contemporary artists and catered to a competing taste that reinvented and upheld cultural coding of the learned communities. By examining painting manuals as sites of cultural negotiation, this study re-evaluates the Japanese reception of Chinese art as a transformative process shaped by increased public access and a shifting vision of the world.