to top

Thesis Topic

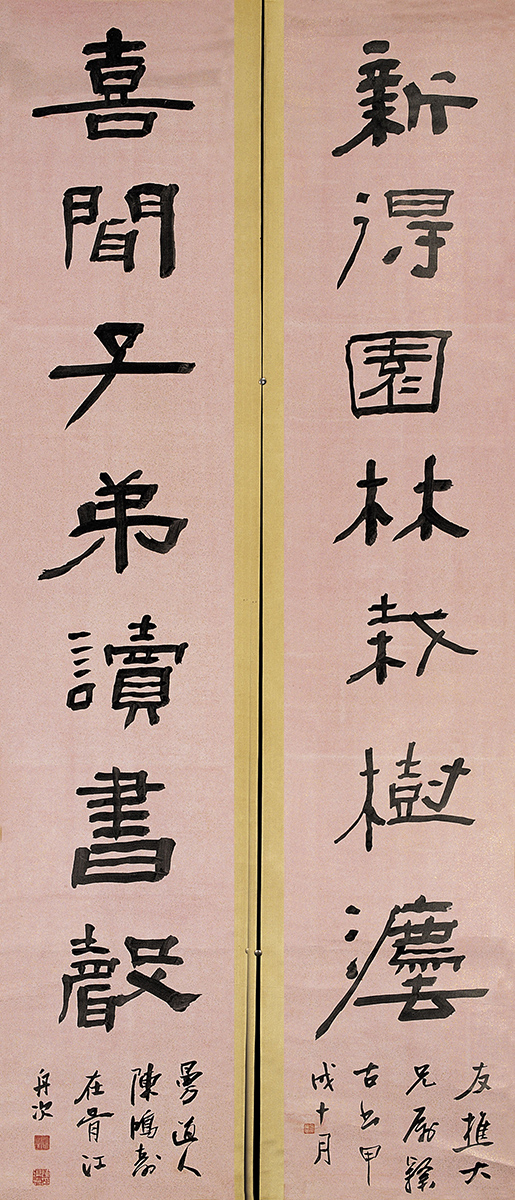

The Qianlong–Jiaqing era witnessed the flourishing of jinshixue (epigraphic and antiquarian studies), as excursions to steles and the collecting of antiquities became major pursuits among scholars. The continual excavation of Han dynasty steles, bronze mirrors, coins, seals, and eave tiles not only propelled empirical scholarship in its mission to verify the classics and supplement history, but also furnished artists with a rich repertoire of forms and motifs. Among the most remarkable figures of this moment was Chen Hongshou (1768–1822), an artist whose practice traversed multiple domains. His seal carving represented a summation of the “Four Members of Xiling” (four renowned seal carvers from Hangzhou); his clerical script calligraphy was recognized on par with Deng Shiru; his paintings were much admired in his time; and his so-called Mansheng teapots circulated with prestige among his literati peers. His artistic production, deeply marked by the intellectual and material culture of the age, offers an ideal lens through which one probes the intersections of antiquarian resources and artistic practice, while also re-examining the conceptual core of Qing art history—the elusive notion of jinshi qi (the epigraphy spirit).

Chen Hongshou was a native of Hangzhou, one of the preeminent hubs of epigraphic collecting in the Qianlong–Jiaqing period. He served for the senior officials Ruan Yuan and Tie Bao and assumed local official posts in Jiangnan afterwards. In cultural centers such as Suzhou, Yangzhou, and Nanjing, he also engaged with an array of collectors as well as artifacts, rubbings, and seal albums. This project brings together textual and visual materials to investigate how, within the burdens of bureaucratic routine, Chen, a local official, fashioned art as a space for self-relief and a leisurely aesthetic mentality. It further traces how his calligraphy, painting, seal carving, and teapot design drew upon epigraphic sources to articulate this distinctive aesthetics. Crucially, Chen’s cultivated leisurely aesthetics infused with a strong scholarly sensibility diverges from the fragmented, ruined epigraphic flavor that came to dominate the late Qing, and yet still constitutes a significant manifestation of jinshi qi. Through the case study of Chen Hongshou, this project asks the question “what is jinshi qi?” and demonstrates how this aesthetic principle—rooted in the antiquarian materiality, craftsmanship, and visual resonance of antiquities (including rubbings)—was narrowly defined and codified in the late Qing.